NRDC re-opens legal battle with Navy, NOAA over sonar

Effects of Noise on Wildlife, News, Ocean, Sonar Comments Off on NRDC re-opens legal battle with Navy, NOAA over sonarThree years after the NRDC and U.S. Navy reached an agreement that was meant to create avenues for dialogue and collaboration, a new lawsuit filed this week suggests that the hopes both sides held have not been realized. The main sticking point remains the same now as it was then: environmental advocates insist that some biologically rich areas should be entirely off limits to any sonar training activity, while the Navy holds that short-term exercises pose no great risk to wildlife. The final Environmental Impact Statements submitted by the Navy, and the permits issued by the NOAA Fisheries Service (which collaborates closely with the Navy in developing guidelines), allow the Navy full access to extensive training ranges that stretch along most of the coastlines of United States. The suit filed this week challenges NOAA permits issued in 2010 for one of the Navy’s dozen or training ranges, off the coast of Washington, Oregon, and northern California. It differs from an earlier high-profile legal challenge, which reached the Supreme Court, in that the previous suit challenged the Navy’s sonar operational guidelines, whereas this one challenges NOAA’s permits.

The Navy is already beginning work on Environmental Impact Statements that will accompany new permit request for all of its ranges, each of which must receive fresh authorization from NOAA every five years. The Navy has recently completed its first-ever EIS’s for training ranges around the world (a process spurred largely by earlier legal challenges); these 5-year permits were issued for some ranges in 2009, and are due for renewal in 2014 and beyond. The operating conditions proposed by the Navy and approved by NOAA for the first-round EISs and permits are generally similar to the way the Navy had been doing things for many years. Marine mammal monitoring is maintained on sonar vessels, with sonar intensity reduced when whales are seen nearby, and operations stopped when whales approach very close to boats. The litigants point out that visual monitoring misses 25-95% of whales, and is particularly ineffective in high seas. “We learn more every day about where whales and other mammals are most likely to be found,” said Heather Trim, director of policy for People for Puget Sound, “We want NMFS to put that knowledge to use to ensure that the Navy’s training avoids those areas when marine mammals are most likely there.”

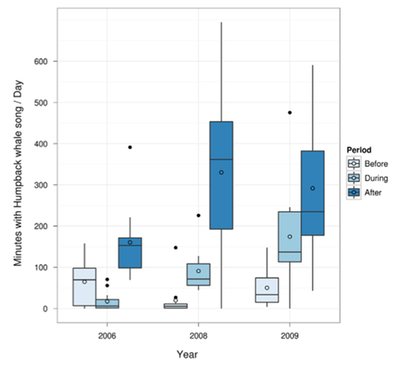

By and large, ocean noise regulations concern themselves only with noise that may be loud enough to cause injury, which occurs only at very close range (under a half mile). More moderate noise, which may cause behavioral changes up to 50 miles away, is assessed in the EIS, but these behavioral changes are generally considered to be of negligible impact to the animals. Recent NOAA permits routinely allow for tens or hundreds of thousands of animals to respond in some way to the sounds of naval maneuvers, with sonars mounted on ships, on floating buoys, and dangled from helicopters being the primary noise source triggering behavioral responses (any behavioral response is considered a “take” in permitting language).

The Navy says that in the Northwest Training Range Complex sonar training exercises typically

Two of the US’s most widely-respected ocean bioacousticians have called for a concerted research and public policy initiative to reduce ocean noise. Christopher Clark, senior scientist and director of Cornell’s Bioacoustics Research Program, and Brandon Southall, former director of NOAA’s Ocean Acoustics Program, recently published

Two of the US’s most widely-respected ocean bioacousticians have called for a concerted research and public policy initiative to reduce ocean noise. Christopher Clark, senior scientist and director of Cornell’s Bioacoustics Research Program, and Brandon Southall, former director of NOAA’s Ocean Acoustics Program, recently published