New gas port proposals adding injury to insult in BC

Ocean, Shipping Comments Off on New gas port proposals adding injury to insult in BCThe British Columbia coast is a wild territory, yet one pockmarked with major shipping facilities. Four related ports stretch down the coast from Prince Rupert, sending coal, grain, and other products to Asian markets and south to the U.S. and beyond. Canadian First Nations and environmental groups have been raising alarms about the cumulative impacts of increased development in this remote area, while innovative ocean noise research is modeling the ways different species’ listening and communication ranges may be affected by more shipping.

Now, plans for two more port facilities, on islands just down the coast from the current Prince Rupert complex, have perhaps gone too far. These are natural gas facilities, next to and literally on top of the Flora Bank, a primary feeding area for juvenile salmon. Project proponents stress that their design will avoid damaging the area, but they seem to be discounting the potentially devastating acoustic impact of the bringing huge ships this close to a sensitive habitat.

Now, plans for two more port facilities, on islands just down the coast from the current Prince Rupert complex, have perhaps gone too far. These are natural gas facilities, next to and literally on top of the Flora Bank, a primary feeding area for juvenile salmon. Project proponents stress that their design will avoid damaging the area, but they seem to be discounting the potentially devastating acoustic impact of the bringing huge ships this close to a sensitive habitat.

Flora Bank, in intertidal waters off Lelu Island, contains about 60 per cent of the eel grass habitat in the Skeena Estuary, a watershed that gives birth to 200 million young salmon each year. This expanse of eel grass is a crucial way station for those that exit out the northern branch of the Skeena (the waterway off the right side of the image above); studies indicate 2-8x more salmon enter the ocean here than in other areas to the south; by some accounts, 90% of the Skeena salmon run comes through here. “It is absolutely clear that Lelu Island is the worst location for such a facility,” says Dimitry Lisitsyn, a Russian biologist who has seen the effects of oil and gas development in his country.

Flora Bank, in intertidal waters off Lelu Island, contains about 60 per cent of the eel grass habitat in the Skeena Estuary, a watershed that gives birth to 200 million young salmon each year. This expanse of eel grass is a crucial way station for those that exit out the northern branch of the Skeena (the waterway off the right side of the image above); studies indicate 2-8x more salmon enter the ocean here than in other areas to the south; by some accounts, 90% of the Skeena salmon run comes through here. “It is absolutely clear that Lelu Island is the worst location for such a facility,” says Dimitry Lisitsyn, a Russian biologist who has seen the effects of oil and gas development in his country.

The companies behind the projects are making efforts to minimize disturbance of the seabed by building a raised pier, jetty, and suspension bridge and will fund the establishment of new seagrass beds nearby, with a goal of doubling the number of young salmon being supported—though similar habitat-creation projects have a spotty success rate. Yet even if they do keep a light physical footprint and avoid creating new sediments that would damage the eelgrass beds, the ships coming into both of the new ports will change the acoustic habitat irrevocably.

Alexander Vedenev, head of the Ocean Noise Laboratory at the Russian Academy of Sciences, says that noise levels from the plant and ships will be audible to young salmon out to about 3km away; some young fish will avoid such sound levels or be startled away with the approach of a ship, while those who linger are likely to experience higher than normal stress levels. Both stress and reduced feeding time can affect long-term survival rates; the worst-case scenario is an abandonment of this crucial feeding ground. The current Ridley Terminals—and shipping lanes serving the other Prince Rupert ports—are just beyond the 3km range, while the new Prince Rupert LNG facility will be 2km from the edge of the Bank, and the Pacific Northwest LNG facility is right on its edge, thus flooding the entire Bank with noise.

So here we have a stretch of wild and beautiful coast, already burdened by significant shipping noise and facing the prospect of many other proposed ports, including a big one at Kitimat, in the lower right of the above image. Now, they want to extend the already-developed stretch of coastline right down to the very edge of an established critical habitat for salmon, building a jetty over the eelgrass itself and dredging a pier area off its outer fringes. This is indeed adding clear injury to an already-existing insult of prime oceanic habitat where the bulk of the Skeena’s salmon travel to and from the sea. How much is enough, folks? Yes, yes, I suppose we could just consider that stretch of coast south of Prince Rupert to be a sacrifice zone; why not extend it right to the lip of the estuary? And I don’t know the area well enough to say with certainty that the salmon can’t find other areas to feed as they make their initial foray from the inland waters of their birth and out into the wild unknown of the seas….but I can easily look at that map above and appreciate the incredible beauty of such a big, wild river, pouring through the mountains from headwaters deep in the heart of British Columbia. Why would we want to desecrate its mouth?

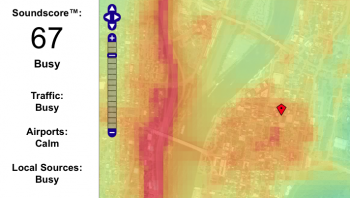

Troy, NY, a mid-sized college and old industrial town along the Hudson River. Note the I-787 corridor on the far side of the river, and the relatively rapid drop-off of neighborhood noise as you move away from the core downtown area.

Troy, NY, a mid-sized college and old industrial town along the Hudson River. Note the I-787 corridor on the far side of the river, and the relatively rapid drop-off of neighborhood noise as you move away from the core downtown area. And my current home in Kennebunk, ME, in a quiet neighborhood. You can see the much smaller downtown noise footprint in the lower right, and the more modest highway noise from the Maine Turnpike on the left.

And my current home in Kennebunk, ME, in a quiet neighborhood. You can see the much smaller downtown noise footprint in the lower right, and the more modest highway noise from the Maine Turnpike on the left.