You may have noticed a recent flurry of press reports about research in Hawaii that begins to quantify a long-suspected quality of cetacean hearing: the ability to dampen hearing sensitivity so that loud sounds don’t cause damage. Given the extremely loud volume of many whale calls, which are meant to be heard tens or hundreds of miles away, researchers have long speculated that animals may have ways of protecting their ears from calls made by themselves or nearby whales, perhaps using a muscle response to reduce their hearing sensitivity (not unlike a similar muscular dampening mechanism in humans). Indeed, earlier studies by Paul Nachtigall’s team had found that some whales could do indeed reduce their auditory response to the sharp clicks they use for echolocation. In the new study, Nachtigall trained a captive false killer whale named Kina to reduce her hearing sensitivity by repeatedly playing a soft trigger sound followed by a loud sound. Eventually, she learned to prepare for the loud sound in advance by reducing her hearing sensitivity. “It’s equivalent to plugging your ears…it’s like a volume control,” according to Nachtigall.

Well, that sounds like a pretty useful trick, given all the concern about human sounds in the sea. And the media, led by the New York Times, jumped on board with headlines following on the Times‘ assertion that suggested whales already “are coping with humans’ din” using this method. (Among the exciting headline variations: Whales Can Ignore Human Noise, Whales Learning to Block Out Harmful Human Noise, and UH Scientists: Whales Can Shut Their Ears.)

Oops, they did it again! Grab some interesting new science and leap to apply a specific finding to a broad public policy question, often, as this time, giving us a false sense of security that the “experts” have solved the problem, so there’s no need to worry our little selves over it any more (as stressed in this NRDC commentary). To be fair, the Times piece included a few cautionary comments from both scientists and environmental groups, but the headline rippled across the web as the story was picked up by others.

Two key things to keep in mind: First, this whale was trained to implement her native ability, meant for use with her sounds or those of nearby compatriots, and to apply it to an outside sound made by humans. This doesn’t mean that untrained whales will do the same.

And second: If whales can dampen their hearing once a loud sound enters their soundscape, this could indeed help reduce the physiological impact of some loud human sounds, such as air guns or navy sonar. If indeed this ability translates to wild cetaceans, the best we could hope for is that it would minimize hearing damage caused by occasional and unexpected loud, close sounds that repeat. There would be no protection from the first blast or two, but perhaps some protection from succeeding ones; or, if the sound source was gradually approaching or “ramping up,” as often done with sonar and air guns, animals may be able to “plug their ears” before sounds reach damaging levels, if for some reason they can’t move away. Even then, the animals are very likely to experience rapidly elevated stress levels, as they would be less able to hear whatever fainter sounds they had been attending to before the intrusion. Yet research in the field suggests that most species of whales and dolphins prefer to keep some distance from such loud noise sources; this hearing-protection trick doesn’t seem to make them happy to hang around loud human sounds.

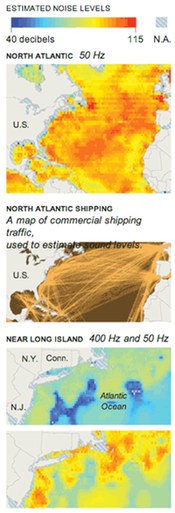

Most crucially, these occasional loud sounds are but a small proportion of the human noises whales are trying to cope with. Noise from shipping, oil and gas production activities, offshore construction, and more distant moderate sounds of air guns all fill the ocean with sound, reducing whales’ communication range and listening area, and likely increasing stress levels because of these reductions. This is the “din” of chronic moderate human noise in the sea, and Kina’s ability would not help her cope with any of it. We’re a long way from being able to rest easy about our sonic impacts in the oceans.

To end this rant with a bit of credit where due, here’s what may be the more important take-away from the Times article:

Peter Madsen, a professor of marine biology at Aarhus University in Denmark, said he applauded the Hawaiian team for its “elegant study” and the promise of innovative ways of “getting at some of the noise problems.” But he cautioned against letting the discovery slow global efforts to reduce the oceanic roar, which would aid the beleaguered sea mammals more directly.

In December, NOAA

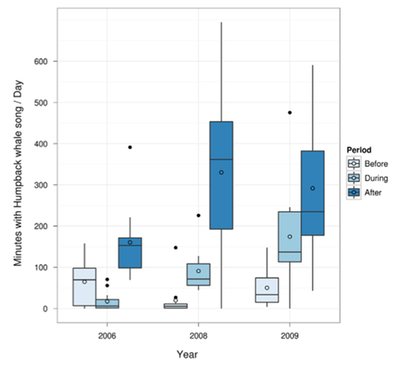

In December, NOAA  Brad Hanson and colleagues at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center are currently conducting a second year of

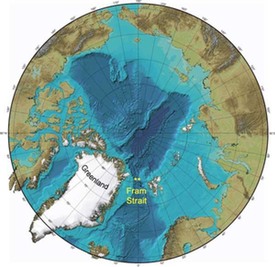

Brad Hanson and colleagues at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center are currently conducting a second year of  When a University of Washington researcher listened to the audio picked up by a recording device that spent a year in the icy waters off the east coast of Greenland, she was stunned at what she heard: whales singing a remarkable variety of songs nearly constantly for five wintertime months. In a paper just published in the journal Endangered Species Research, and freely available online, Kate Stafford and her co-authors report on acoustic monitoring that took place in the winter of 2008-9 in the Fram Strait, between Greenland and Spitzbergen, a key channel for water circulation between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans.

When a University of Washington researcher listened to the audio picked up by a recording device that spent a year in the icy waters off the east coast of Greenland, she was stunned at what she heard: whales singing a remarkable variety of songs nearly constantly for five wintertime months. In a paper just published in the journal Endangered Species Research, and freely available online, Kate Stafford and her co-authors report on acoustic monitoring that took place in the winter of 2008-9 in the Fram Strait, between Greenland and Spitzbergen, a key channel for water circulation between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans.

Bernie Krause’s new book,

Bernie Krause’s new book,  Two of the US’s most widely-respected ocean bioacousticians have called for a concerted research and public policy initiative to reduce ocean noise. Christopher Clark, senior scientist and director of Cornell’s Bioacoustics Research Program, and Brandon Southall, former director of NOAA’s Ocean Acoustics Program, recently published

Two of the US’s most widely-respected ocean bioacousticians have called for a concerted research and public policy initiative to reduce ocean noise. Christopher Clark, senior scientist and director of Cornell’s Bioacoustics Research Program, and Brandon Southall, former director of NOAA’s Ocean Acoustics Program, recently published

Many such small crustaceans are foundations of vast ocean food webs. Co-author

Many such small crustaceans are foundations of vast ocean food webs. Co-author