AEI lay summary of Rob Williams, Christine Erbe, Erin Ashe, Christopher Clark. Quiet(er) marine protected areas. Marine Pollution Bulletin (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.marpolbul.2015.09.012 View or download paper online

Over the past decade or so, concern about ocean noise has expanded from its initial focus injuries and deaths caused by periodic loud events, such as sonar or seismic surveys. Many researchers are now working to understand the ways that widespread, chronic shipping noise affects marine creatures’ behavior, foraging success, and stress levels. Long-term deployment of hydrophones, sound models that extrapolate from shipping data, and slow-but-steady improvements in our knowledge of the hearing ranges and population densities of particular species have all combined to open exciting new avenues for research that can inform policy decisions in the years to come.

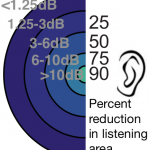

Using these new measurement and modeling techniques, researchers can quantify the “acoustic quality” of marine habitats. This starts with charting the extent of shipping noise, while also considering the different auditory ranges of various species of interest. Next, researchers map where animals tends to congregate in various seasons, to identify areas that are especially important to each species.

Of particular importance is identifying areas that have, so far, remained relatively free of shipping noise. If at all possible, we’ll want to avoid extending the human noise footprint into these increasingly rare acoustic havens. A research team that’s been active on Canada’s southwest coast over the past few years has been at the forefront of these techniques, and has just published a new paper that introduces the concept of “opportunity sites”—areas used by each species that are still relatively quiet, and so have high long-term conservation value.

“We tend to focus on problems in conservation biology. This was a fun study to work on, because we looked for opportunities to protect species by working with existing patterns in noise and animal distribution, and found that British Colombia offers many important habitat for whales that are still quiet,” said Dr. Rob Williams, lead author of the study. “If we think of quiet, wild oceans as a natural resource, we are lucky that Canada is blessed with globally rare pockets of acoustic wilderness. It makes sense to talk about protecting acoustic sanctuaries before we lose them.”

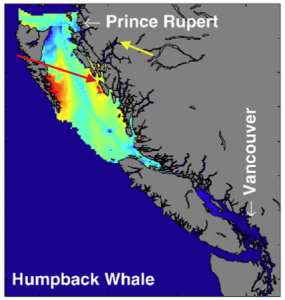

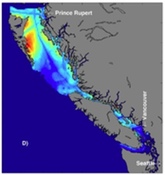

Below left: population density of harbor porpoise in coastal waters of British Columbia; below center: ship noise, weighted to harbor porpoise hearing; below right: opportunity sites to preserve high-quality acoustic habitat for harbor porpoises. Red indicates “highest”, blue “lowest” on all maps.

These new opportunity maps make it painfully obvious how little of each species’ habitat is free of excessive shipping noise. In the example above, harbor porpoises can only find high quality acoustic habitat in a couple of small areas. Without some concerted effort to protect these areas, they will continue to shrink.

While recognizing that many areas of critical habitat are already too loud (in particular, the entire Seattle/Vancouver region), the authors acknowledge that reducing existing noise is difficult—limiting shipping, or reducing the noise made by boats, has social and economic costs that can be hard to accept. By contrast, the areas they’ve identified merely need to be maintained in close to their current acoustic condition, which will be far easier to accomplish. As the authors note:

In our professional opinion, if two places are equally important to whales, with one being noisy and the other being quiet, it would be helpful to identify those areas and present that information to decision-makers. The noisy area may require mitigation, whereas the quiet area may make a more attractive or convenient candidate for critical habitat protection, either because it represents higher quality habitat to the animals or because it imposes lower economic costs to society to mitigate anthropogenic threats.

This may not mean excluding new activities from these regions, because, again in the authors’ words, “a particular marine environment could be dominated by anthropogenic underwater noise that is perceived as being loud to one species, but quiet to another.” Indeed, the opportunity maps differ for each species (though that area on the eastern side of the large island of Haida Gwaii recurs in most). So, we will need to pay close attention to what species are present, how well they’ll hear the new noise sources, and the ways they may respond.

Generally, large ship noise is far more audible for baleen whales (humpback, fin, etc.) than for smaller toothed whales (dolphins, orca), which vocalize and hear at higher frequencies. That’s not to say that the smaller whales don’t hear big ships; they often do, and in many cases, they respond at a lower sound level than larger whales, so even if the ships are “fainter” to their ears, their reactions may be similar.

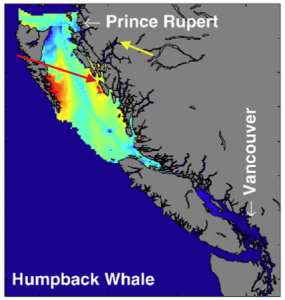

While this paper steers clear of any sort of advocacy tone, and does no more than present the new “opportunity sites” analysis and mapping technique, the waters being studied are at the center of a contentious public policy debate. The proposed Northern Gateway pipeline from the oil sands region of Alberta would dramatically increase tanker traffic to the existing deep-water port at Kitimat (yellow arrow, left). Such an increase through Caamano Sound (red arrow, left) would threaten the humpback whale opportunity site (map, left) identified just south of the Sound. Several years ago, co-author Rob Williams told reporters, “Caamano Sound may be one of the last chances we have on this coastline to protect an acoustically quiet sanctuary for whales. … We don’t exactly know why this area is so rich, but there are some long, narrow channels that serve as bottlenecks for food, making it easier for whales to feed.” A consortium of environmental organizations is currently challenging the Canadian government’s approval of the pipeline, claiming that the approval did not take into account the humpback recovery plan, identifying Hecate Strait (the larger area between the mainland and the large offshore island) as a critical humpback feeding ground. The pipeline is being challenged on several fronts (including strong opposition from B.C. First Nations communities); considering acoustic habitat protection, limiting new ship traffic during the times of year when the current opportunity sites are being heavily used would seem to be the least we can do.

While this paper steers clear of any sort of advocacy tone, and does no more than present the new “opportunity sites” analysis and mapping technique, the waters being studied are at the center of a contentious public policy debate. The proposed Northern Gateway pipeline from the oil sands region of Alberta would dramatically increase tanker traffic to the existing deep-water port at Kitimat (yellow arrow, left). Such an increase through Caamano Sound (red arrow, left) would threaten the humpback whale opportunity site (map, left) identified just south of the Sound. Several years ago, co-author Rob Williams told reporters, “Caamano Sound may be one of the last chances we have on this coastline to protect an acoustically quiet sanctuary for whales. … We don’t exactly know why this area is so rich, but there are some long, narrow channels that serve as bottlenecks for food, making it easier for whales to feed.” A consortium of environmental organizations is currently challenging the Canadian government’s approval of the pipeline, claiming that the approval did not take into account the humpback recovery plan, identifying Hecate Strait (the larger area between the mainland and the large offshore island) as a critical humpback feeding ground. The pipeline is being challenged on several fronts (including strong opposition from B.C. First Nations communities); considering acoustic habitat protection, limiting new ship traffic during the times of year when the current opportunity sites are being heavily used would seem to be the least we can do.

They look small, about the size of a “cherry bomb” firecracker. They’re legal, exempt from the Marine Mammal Protection Act thanks to their functional purpose: protecting fishermen’s nets from seals and cetaceans poaching their catches, including squid, anchovies, and tuna.

They look small, about the size of a “cherry bomb” firecracker. They’re legal, exempt from the Marine Mammal Protection Act thanks to their functional purpose: protecting fishermen’s nets from seals and cetaceans poaching their catches, including squid, anchovies, and tuna.

The recent

The recent  In yet another unforeseen consequence of global warming, scientists have begun charting the extent of a new underwater sound channel in the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska. As

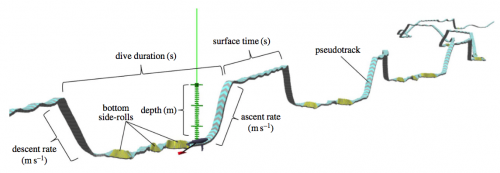

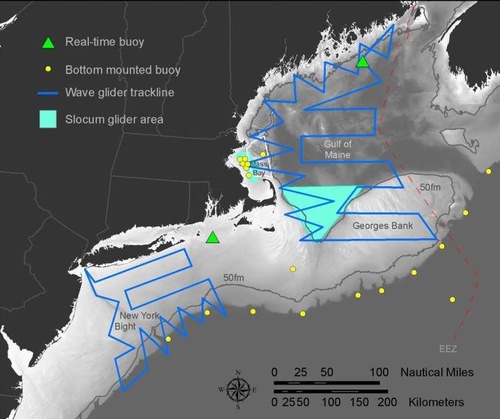

In yet another unforeseen consequence of global warming, scientists have begun charting the extent of a new underwater sound channel in the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska. As  A new study looks for the first time at the impact of human noise on an important type of humpback whale foraging activity, bottom-feeding on sand lance. The research took place in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in the southern Gulf of Maine, where humpback whales routinely do deep dives at night, rolling to their sides when they reach the bottom to forage for the small fish.

A new study looks for the first time at the impact of human noise on an important type of humpback whale foraging activity, bottom-feeding on sand lance. The research took place in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in the southern Gulf of Maine, where humpback whales routinely do deep dives at night, rolling to their sides when they reach the bottom to forage for the small fish.

This post from NRDC

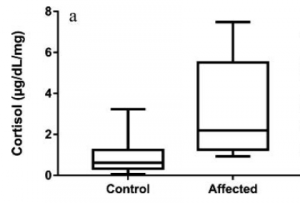

This post from NRDC The overall results are fairly clear-cut. Here’s a graph of the two groups; the boxes show the 3 quartiles of results in each group (the bottom of the box being the level that 75% of the animals were above; the line across the box showing the level where half the animals were above, half below; and the top of the box the level that 25% of the animals were above), with the bars outside the box showing the remaining scatter of individuals. The mean among controls was .87, and among the affected group the mean was 3.16

The overall results are fairly clear-cut. Here’s a graph of the two groups; the boxes show the 3 quartiles of results in each group (the bottom of the box being the level that 75% of the animals were above; the line across the box showing the level where half the animals were above, half below; and the top of the box the level that 25% of the animals were above), with the bars outside the box showing the remaining scatter of individuals. The mean among controls was .87, and among the affected group the mean was 3.16 A closer look at the results suggests that, as usual in field studies, there is a lot more going on than the means and medians suggest. Here we see a plot of the 9 affected setts, with distance to nearest turbine on the bottom axis. Interestingly, there is a wide scatter of results, with some setts (2 of the 9) showing levels very similar to the controls, about half (4 of the 9) having somewhat elevated levels, and only 3 setts being highly elevated, above the highest of the control setts. Our first image shows this skew, with the upper quartile of the affected box stretching far above the middle line (and thus pulling up the mean to a significant degree).

A closer look at the results suggests that, as usual in field studies, there is a lot more going on than the means and medians suggest. Here we see a plot of the 9 affected setts, with distance to nearest turbine on the bottom axis. Interestingly, there is a wide scatter of results, with some setts (2 of the 9) showing levels very similar to the controls, about half (4 of the 9) having somewhat elevated levels, and only 3 setts being highly elevated, above the highest of the control setts. Our first image shows this skew, with the upper quartile of the affected box stretching far above the middle line (and thus pulling up the mean to a significant degree).

They also heard large ships coming in “loud and strong,” and even the calls of a smaller toothed whale or dolphin relatively near the surface; you can

They also heard large ships coming in “loud and strong,” and even the calls of a smaller toothed whale or dolphin relatively near the surface; you can

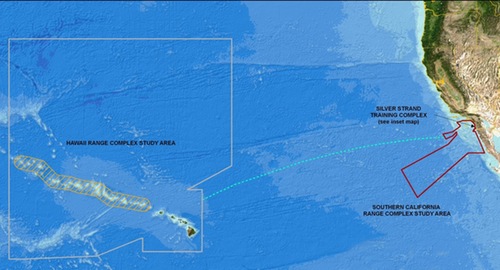

But while scientists are keen to hear what the new undersea recordings have to tell us, the US and Canadian Navies are far less enthusiastic. They’re concerned that the audio feeds, which are freely available to scientists and the public as downloads and via live online feeds, will reveal sensitive information about submarine and ship movements, navy training activities, and even the sound signatures of individual vessels. The two navies have arranged with researchers to have an audio bypass switch that allows them to divert the audio streams into a secured military computer—sitting in a locked cage at the research facility where the data comes ashore—at times when their ships are nearby (and also at some random other times, so that their diversions don’t give away any secrets on their own!).

But while scientists are keen to hear what the new undersea recordings have to tell us, the US and Canadian Navies are far less enthusiastic. They’re concerned that the audio feeds, which are freely available to scientists and the public as downloads and via live online feeds, will reveal sensitive information about submarine and ship movements, navy training activities, and even the sound signatures of individual vessels. The two navies have arranged with researchers to have an audio bypass switch that allows them to divert the audio streams into a secured military computer—sitting in a locked cage at the research facility where the data comes ashore—at times when their ships are nearby (and also at some random other times, so that their diversions don’t give away any secrets on their own!).  One study is further along, having

One study is further along, having  She said the sound of “bait balls” of prey, such as schools of fish, could be greatly heightened when a feeding frenzy involving larger fish and seabirds broke out. Dr Constantine said whales had been observed swimming rapidly from over a kilometre away toward prey aggregations, “so we’re very interested to find out if there are specific acoustic cues they home in on”.

She said the sound of “bait balls” of prey, such as schools of fish, could be greatly heightened when a feeding frenzy involving larger fish and seabirds broke out. Dr Constantine said whales had been observed swimming rapidly from over a kilometre away toward prey aggregations, “so we’re very interested to find out if there are specific acoustic cues they home in on”.