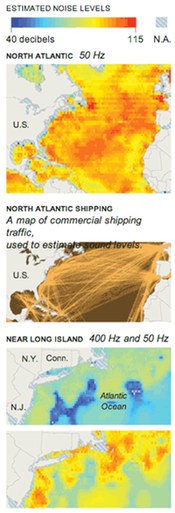

In the wake of NOAA’s large-scale ocean noise mapping project, two much more detailed studies from the Pacific Northwest have highlighted the likelihood that current shipping noise is already pushing the limits of what biologists think many ocean creatures can cope with.

In the wake of NOAA’s large-scale ocean noise mapping project, two much more detailed studies from the Pacific Northwest have highlighted the likelihood that current shipping noise is already pushing the limits of what biologists think many ocean creatures can cope with.

The first study recorded the sound from several types of boats and ships traversing Admiralty Inlet, between Whidbey Island and Port Townsend, WA, and used these recordings, correlated with ship traffic records, to model sound levels throughout the area. The Seattle Times summarizes this work, which found that at least one large vessel (container ship, ferry, or large tug) was in the area at least 90% of the time, and that the average noise level was about 120 decibels, which is the threshold above which federal agencies begin being concerned about behavioral impacts on some ocean species.

“Continuous noise at that level is considered harassment of marine mammals,” said University of Washington’s Christopher Bassett, one of the authors of the paper. “About 50 percent of the time, we even exceed that threshold.”

“It is concerning that the noise levels are so high,” said Marla Holt, a research biologist at Seattle’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center. “When you see how often this happens and how chronic the noise exposure is, that’s when you start to say, ‘Wow.'”

Interlude: Brief OrcaLab recording of threatened Northern Resident killer whales in Caamano Sound, BC, chatting with each other and then being drowned out by a cruise ship:

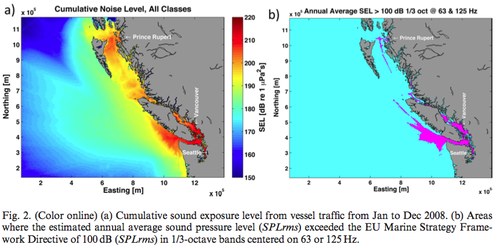

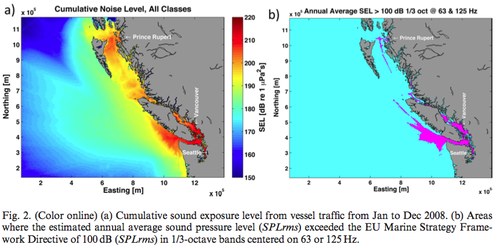

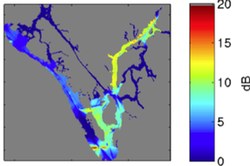

To the north, another study mapped shipping noise in the Salish Sea (south and east of Vancouver Island), and on up the British Columbia coast to the port of Prince Rupert. This work, funded by World Wildlife Fund-Canada, introduces a comprehensive approach to modeling sound transmission from ships, incorporating differences between vessel types, transmission loss in a variety of bathymetric and seabed conditions, and temperature-driven variations in sound speed during different seasons. (Download a PDF presentation summarizing the full WWF-Canada report here; a shorter version appeared in JASA in November). Here, too, large areas are subject to excessive shipping noise; the maps below show total sound levels, and the areas where the annual average of two specific low frequencies are above the 100dB threshold that the European Union considers the target for biologically sensitive areas:

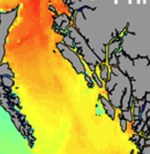

But now, check out that lighter colored patch about halfway between BC’s two big offshore islands.

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again—so more than one passage a day on average). As you might imagine, there is widespread concern about the risks of accidents and spills in these often treacherous passages, but the increase in shipping noise is also being raised as a question.

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again—so more than one passage a day on average). As you might imagine, there is widespread concern about the risks of accidents and spills in these often treacherous passages, but the increase in shipping noise is also being raised as a question.

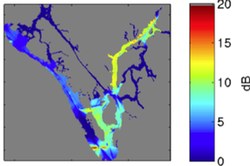

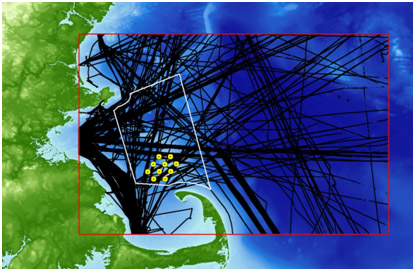

A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy.

A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy.

“There is a worry they will go away and not come back to these fiords,” says Erbe. “This is critical habitat, important to them. Are they going to be able to feed elsewhere? We can only answer that with long-term monitoring.”

These studies, one of which utilized four seasons of recordings, and the other presenting a comprehensive and verifiable sound modeling approach, both offer exciting steps forward in the study of coastal and oceanic acoustic habitats. Let’s hope that coming years produce many more studies from other regions around the world that continue to develop these innovative techniques.

Detailed Northern Gateway study: Erbe, C., Duncan, A., and Koessler, M. 2012. Modelling noise exposure statistics from current and projected shipping activity in northern British Columbia. Report submitted to WWF Canada by Curtin University, Australia.

BC sound modeling study: Erbe, C., MacGillivray, A., and Williams, R. 2012. Mapping Ocean Noise: Modelling Cumulative Acoustic Energy from Shipping in British Columbia to Inform Marine Spatial Planning. Report submitted to WWF Canada by Curtin University, Australia.

Shorter version: Erbe, C., MacGillivray, A., and Williams, R. 2012. Mapping cumulative noise from shipping to inform marine spatial planning. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 132 (5), November 2012. 423-428.

Puget Sound study: Bassett, C., Polagye, B., Holt, M., Thomson, J. 2012. A vessel noise budget for Admiralty Inlet, Puget Sound, Washington (USA). J.Acoust.Soc.Am. 132(6), December 2012

Related:

Kathy Heise and Hussein Alidina. Ocean Noise in Canada’s Pacific Workshop, January 31-February 1, 2012. Summary Report. WWF-Canada. 54pp. Read or download PDF

WWF-Canada Submission to Enbridge Northern Gateway Joint Review Panel, 9/19/12. (mostly terrestrial impacts; some ocean noise sections) Read or download PDF

For over a decade, the National Park Service has been on the forefront of public lands agencies in addressing the role of sound and noise on both wildlife and park visitors. NPS’s Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division has catalyzed baseline acoustic monitoring in seventeen parks, and carried out groundbreaking research on the effects of noise on wildlife.

For over a decade, the National Park Service has been on the forefront of public lands agencies in addressing the role of sound and noise on both wildlife and park visitors. NPS’s Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division has catalyzed baseline acoustic monitoring in seventeen parks, and carried out groundbreaking research on the effects of noise on wildlife.

Add crabs, and perhaps by extension other crustaceans, to the list of animals negatively affected by shipping noise in the world’s oceans.

Add crabs, and perhaps by extension other crustaceans, to the list of animals negatively affected by shipping noise in the world’s oceans.

Watching the decade-long struggle in Massachusetts to build Cape Wind, the nation’s first offshore wind farm, researchers and state officials in Maine have chosen a different path: they decided to tackle the engineering challenges of building turbines that can float in deep water far offshore, rather than the social challenges of building wind farms in shallow water close to shore (which use fundamentally the same foundation designs as onshore turbines). Floating deepwater turbines can take advantage of even stronger, more consistent winds than their nearshore counterparts; along most of the east coast, offshore wind is far more reliable than onshore locations.

Watching the decade-long struggle in Massachusetts to build Cape Wind, the nation’s first offshore wind farm, researchers and state officials in Maine have chosen a different path: they decided to tackle the engineering challenges of building turbines that can float in deep water far offshore, rather than the social challenges of building wind farms in shallow water close to shore (which use fundamentally the same foundation designs as onshore turbines). Floating deepwater turbines can take advantage of even stronger, more consistent winds than their nearshore counterparts; along most of the east coast, offshore wind is far more reliable than onshore locations.

In the wake of

In the wake of

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy.

A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy. In December, NOAA

In December, NOAA  Brad Hanson and colleagues at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center are currently conducting a second year of

Brad Hanson and colleagues at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center are currently conducting a second year of

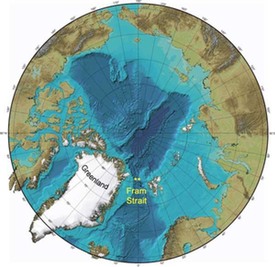

When a University of Washington researcher listened to the audio picked up by a recording device that spent a year in the icy waters off the east coast of Greenland, she was stunned at what she heard: whales singing a remarkable variety of songs nearly constantly for five wintertime months. In a paper just published in the journal Endangered Species Research, and freely available online, Kate Stafford and her co-authors report on acoustic monitoring that took place in the winter of 2008-9 in the Fram Strait, between Greenland and Spitzbergen, a key channel for water circulation between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans.

When a University of Washington researcher listened to the audio picked up by a recording device that spent a year in the icy waters off the east coast of Greenland, she was stunned at what she heard: whales singing a remarkable variety of songs nearly constantly for five wintertime months. In a paper just published in the journal Endangered Species Research, and freely available online, Kate Stafford and her co-authors report on acoustic monitoring that took place in the winter of 2008-9 in the Fram Strait, between Greenland and Spitzbergen, a key channel for water circulation between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans.