While I was certainly glad to hear that President Obama has declared most of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas in the Alaskan arctic “indefinitely off limits” to oil and gas development, the roar of approval from the media and environmentally-minded public was louder than the action actually merits. And the Atlantic withdrawals appear next to meaningless. I know we should never look a gift horse in the mouth, but even a quick glance reveals more gum than enamel in this one. Nonetheless, I’ll take an over-enthusiastic celebratory shout over even the fading ghost of the chance of much more enduring and disruptive roars from seismic surveys, crazy-loud engines on stabilized drilling platforms, and decades of crew transport and tanker traffic. It’s not for nothing that diverse group of scientists and activists have been calling on Obama to do just this for the past couple of years.

Still, I’m here to temper the joy. Before looking at the maps that put the modest impact of this move in perspective, there’s a red flag right up top that deserves a bit more clarification. All commenters, enviros and energy companies alike, seem to agree that this withdrawal is more consequential than the November announcement by the Department of Interior that no lease sales would be offered in either the Arctic or Atlantic for the upcoming 2017-2022 leasing period, a decision that’s won’t be finalized until July and could have been vulnerable to reversal by the incoming administration. Obama’s new declaration likely closes the door on such a rapid reconsideration of these upcoming five-year plans. But notice that the magic word in the withdrawals is “indefinitely,” not “permanently.” It seems that the door is left open to reconsideration: the White House statement detailing the withdrawal states that the “indefinitely off limits” designation is “to be reviewed every five years through a climate and marine science-based life-cycle assessment.” (To be fair, the text is somewhat ambiguous as to whether this 5-year review applies to both the US and Canadian actions, or just the latter.)

UPDATE, 1/11/17: The outgoing administration tied up a worrisome loose end this week by denying six pending applications to do exploratory seismic surveys in the Mid- and South-Atlantic planning areas. This is a one-time denial; future re-applications can be considered at any time. New surveys will be necessary to inform any future lease sales in these areas.

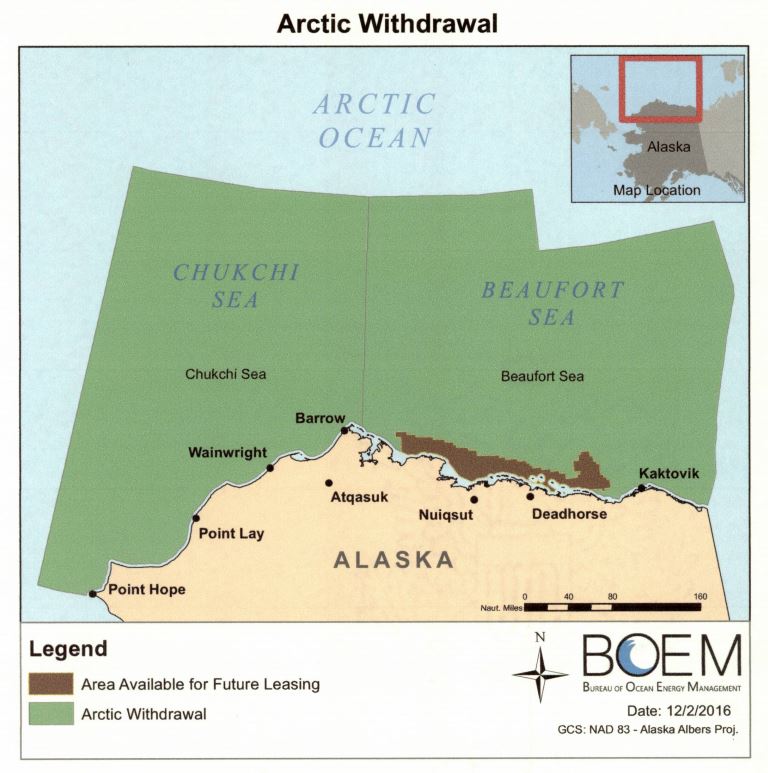

So for now, let’s celebrate that at least the first term of a Trump administration has its hands fairly well tied in its ambitions to expand US offshore oil production from its current focus on the Gulf of Mexico and in a 200 mile strip of waters along Alaska’s Arctic coast. Wait, what’s that? Yep, the big withdrawal announcement doesn’t remove any of the areas already being actively developed off Alaska’s northern shores (brown in this map):

The good news is that there are currently only a handful of producing wells in that brown strip, on three of the five lease areas owned by one company, Hilcorp, just offshore from Deadhorse (they’re the tiny green areas in the next map, below). In fact, out of the peak of 480 lease tracts in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas that had been acquired by energy companies as of 2008, only 43 leases (including 53 lease blocks) are still even nominally in the planning pipeline; 42 of them are in this area that remains available to future leasing as well. Falling oil prices, disappointing test well production, and both logistical and increased regulatory hurdles have led many of the companies that were once so enthused about moving into these waters to formally abandon their leases.

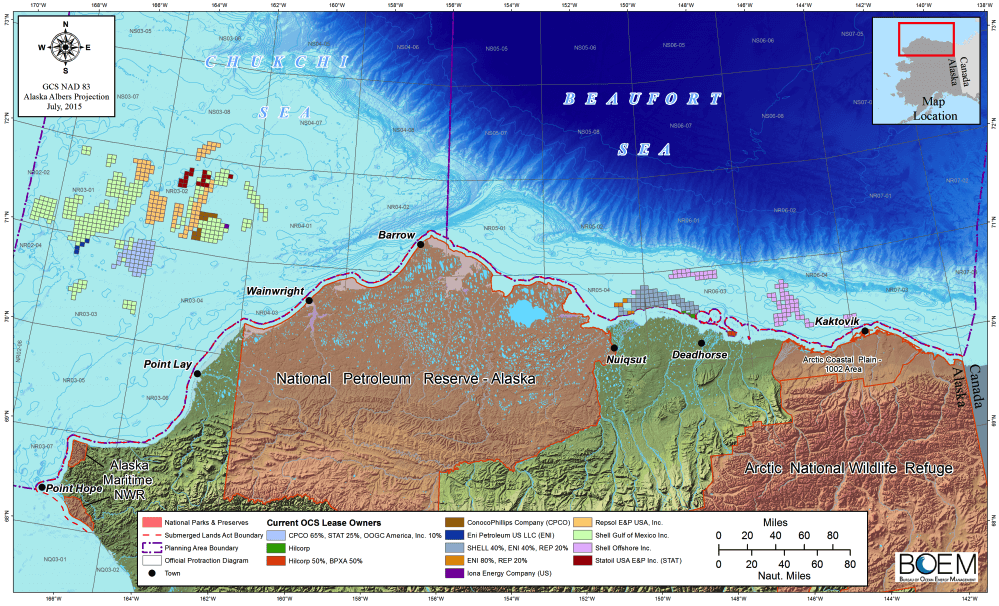

Here’s a look at where things stood as recently as July 2015, when the Chukchi was still the focus of industry hopes and dreams:

(right click to see a larger version)

Shell was the biggest of 12 corporate players (lime green in the Chukchi, grey in the Beaufort), and took the lead on offshore exploration and test well drilling. But in the face of unrelenting bad news, they began abandoning their plans. After fighting for a while to extend several leases set to expire in 2017, by the middle of this year Shell formally relinquished all but one Chukchi lease (set to expire in 2020) and abandoned their legal challenges to extend those expiring sooner. Meanwhile, all the other Chukchi lease holders shown on the map above, including Statoil, Eni, and Repsol, have also relinquished their leases, leaving the single Shell tract as the only active lease in the basin. Interestingly, the one they’re holding on to is the one where they drilled their test well; while the results there were reported as disappointing, they’re not giving up on its potential.

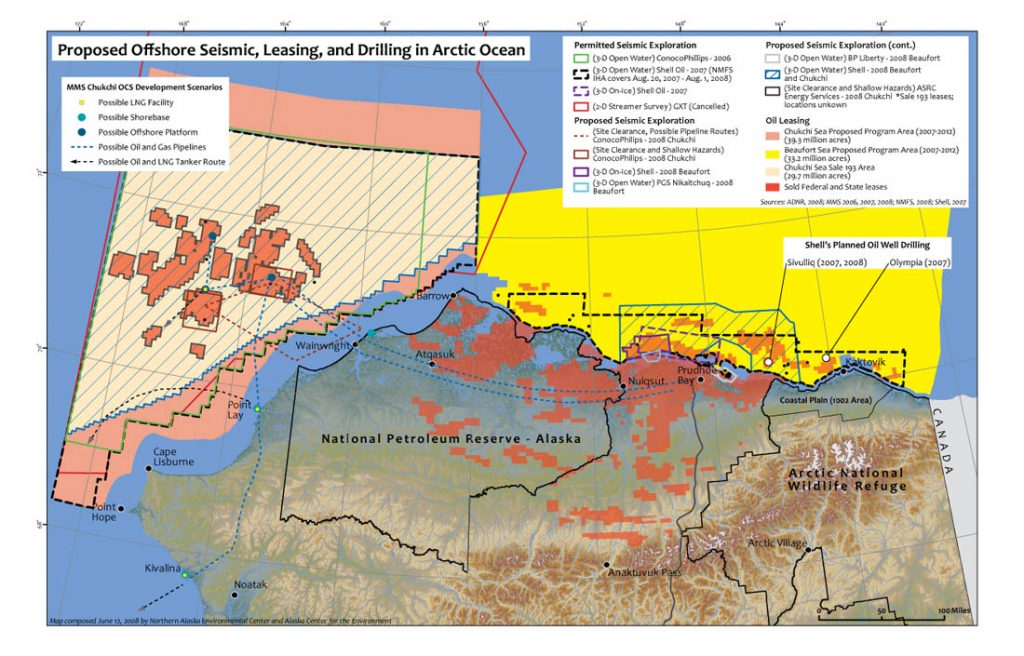

Speaking of potential, take a gander at the Grand Vision that was driving all these companies in 2007:

Again, you can click to enlarge: check out the offshore pipelines, tanker routes, seismic survey areas that, by and large, never came to pass. Now, with all but that one Shell lease abandoned, it’s relatively easy for the Obama team to shut down the tan Chukchi zone shown here, and to contract the yellow Beaufort zone to include just the near-shore areas where the industry is most interested in staying active. A close comparison of the withdrawal map and this one suggests that most of the orange areas in the Beaufort targeted for development in 2007 are still on the table; a few of the bits that are furthest offshore as well as those in the eastern end of the yellow zone are now in the exclusion zone. Though remember: even it what remains, the feds are not offering any new leases for the 2017-22 period.

Industry interest in offshore development has not completely evaporated, but it’s getting pretty meager. In December, the Alaska Division of Oil and Gas was “surprised” at the number of bids they received in a new leasing round, and touted the numbers to emphasize the shortsightedness of Obama’s action. The vast majority of the sites were on the North Slope, but seven offshore leases were snapped up in state waters adjacent to the federal Beaufort leasing zone (they’re pink and orange on this map); six of these attracted a lone bidder, new to Alaska—which either indicates that there’s continued fresh enthusiasm or suggests that these sites are likely to join the long list of leased offshore areas that never make it into development.

Plenty of oil and gas deposits remain available in Alaska, including that 200-mile swath of coastal waters and vast expanses of onshore territory (not least the huge National Petroleum Reserve, which also attracted a new wave of lease bids in December). Nationwide, the vast majority of offshore oil is still in the Gulf of Mexico; when announcing the 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf leasing plan that excluded Arctic and Atlantic waters, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) Director Abigail Hopper stressed that “The proposal makes available more than 70% of the economically recoverable resources, which is ample opportunity for oil and gas development to meet the nation’s energy needs.” (The qualifier “economically recoverable” is undoubtedly open to varied interpretation; but suffice to say that 70% number would be larger if it counted these near-shore Alaskan waters and areas in the Atlantic that are excluded in her count for that particular five-year plan.)

All in all, the Arctic moves look like a signature Obama approach, very much in keeping with previous actions on Alaskan oil and gas: he keeps the door open, avoiding permanent prohibitions, all the while knowing that the global oil market and emerging social pressures will impose far more effective and permanent limits on the potential for actual offshore development than heavy-handed government decisions.

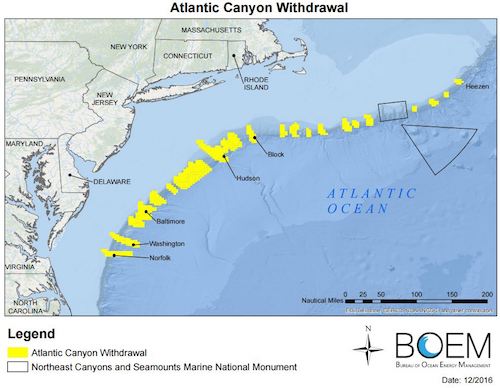

The same thinking may be in play over in the Atlantic, though the scope of even this non-permanent withdrawal is extremely limited there. Here’s map of “indefinite” Atlantic withdrawals:

That’s excellent! We’re going to protect a long string of biologically productive canyons along the continental shelf. Hip hip.

But only the two southernmost of these canyons are actually part of BOEM’s long-term offshore oil and gas development zones anyway; see the map at the right for a look at the two large planning areas that were pulled out of the leasing process for 2017-22. At this point, there is no plan to re-open the North Atlantic Planning Area to offshore exploration and development; of course, this could quickly change with the incoming administration, so again, Obama’s action may keep that idea from gaining a foothold in the next four years. The withdrawal action is nearly certain to be challenged in court, but by the time it works its way through the legal process, even if it’s overturned there wouldn’t be time to do more than initiate the multi-year Programmatic EIS process that would be the first step of re-opening northeastern waters to development.

But only the two southernmost of these canyons are actually part of BOEM’s long-term offshore oil and gas development zones anyway; see the map at the right for a look at the two large planning areas that were pulled out of the leasing process for 2017-22. At this point, there is no plan to re-open the North Atlantic Planning Area to offshore exploration and development; of course, this could quickly change with the incoming administration, so again, Obama’s action may keep that idea from gaining a foothold in the next four years. The withdrawal action is nearly certain to be challenged in court, but by the time it works its way through the legal process, even if it’s overturned there wouldn’t be time to do more than initiate the multi-year Programmatic EIS process that would be the first step of re-opening northeastern waters to development.

So, the bottom line: this big new withdrawal action doesn’t actually take any areas that are currently in the leasing pipeline out of action. It does slightly reduce the size of the zone off Alaska’s northern coast that is routinely part of the BOEM’s 5-year leasing cycle, and it may slow down attempts by the Trump crew to kickstart fresh offshore development before 2022. If it survives its legal gauntlet (culminating in a regulation-averse Supreme Court), then the withdrawal will spare the high-risk far offshore Arctic waters from inclusion in future 5-year planning cycles (though only for an “indefinite” period); meanwhile, the two primary Atlantic planning areas are still fair game for the next round. With no active production planned in any of the withdrawn areas, even without these actions we were many years, likely a decade or two, away from any new Arctic offshore or Atlantic canyons oil flowing into refineries. Turning off any fossil fuel spigot is a good thing—at least if it stays off—but we have to acknowledge that these actions did not affect any current or planned spigots, and so have not reduced our climate footprint by one iota, either immediately or over foreseeable future. Sad to say, but true.

So now you know “the rest of the story,” to steal Paul Harvey’s tagline. I’m not exactly sure why it felt like a story needing telling; most likely I’m just hyper-sensitive to headlines and press releases that oversimplify issues I care about. I definitely can’t begrudge my fellow earth warriors the chance to feel like something went our way at last. And I am certainly grateful for each and every day that these waters will be spared the noise intrusions of 21st century offshore oil and gas development. This is a rare bit of good news. Sorry to be the one pointing out the “bit” of it….