New paper quantifies shipping noise impact on whale communication space

Effects of Noise on Wildlife, Ocean, Science Add commentsThe latest paper to be published by the research team that’s been studying noise levels in and around the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary concludes that in the waters off Boston, increasing shipping noise has reduced the area over which whales can hear each other to about one-third of what it used to be.

“We had already shown that the noise from an individual ship could make it nearly impossible for a right whale to be heard by other whales,” said Christopher Clark, Ph.D., director of Cornell’s bioacoustics research program and a co-author of the work. “What we’ve shown here is that in today’s ocean off Boston, compared to 40 or 50 years ago, the cumulative noise from all the shipping traffic is making it difficult for all the right whales in the area to hear each other most of the time, not just once in a while. Basically, the whales off Boston now find themselves living in a world full of our acoustic smog.”

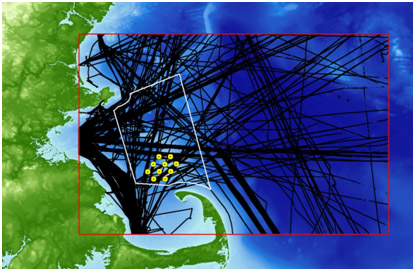

Below: Ship tracks for one month, in and out of Boston; Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary outlined in white, bottom-mounted recording units in yellow. (Graphics from NOAA’s Passive Acoustic Monitoring website)

“A good analogy would be a visually impaired person, who relies on hearing to move safely within their community, which is located near a noisy airport,” said Leila Hatch, Ph.D., NOAA’s Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary marine ecologist. “Large whales, such as right whales, rely on their ability to hear far more than their ability to see. Chronic noise is likely reducing their opportunities to gather and share vital information that helps them find food and mates, navigate, avoid predators and take care of their young.”

Nine hours in Stellwagen:

Kathy Metcalf of the Chamber of Shipping of America said her group has no doubt noise is increasing and affecting the whales. But measures such as slowing down ships or retrofitting them with new, more efficient propellers are costly and may not even work, she said. A better remedy would be devising and incorporating quieter designs in the hulls and propellers of new vessels. “We’re kind of a slow industry,” Metcalf said. “But the bottom line is if we could do something now that can be used as guidelines for new construction, 15 years from now, half the world’s fleet would have already been built that way.”

Bonus: 2010 Science magazine audio interview with Leila Hatch, lead author of the new paper.